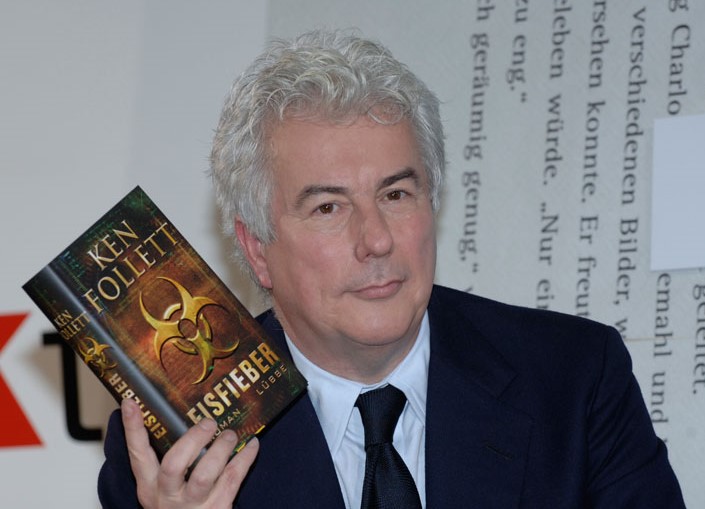

In last Saturday’s Telegraph supplement there was a piece about best selling novelist Ken Follet. I had been thinking about him recently because I need to get a historical novel of his that touches on the Huguenots, as I plan to write a novel about them.

Follet told us how he was raised in a Christian family, adhering to the very strict Plymouth Brethren sect, about which I know a little from direct contact. There was no television allowed etc. He said in the Telegraph article that as he grew up, he asked his father why the Bible could be relied on. Follet didn’t enlarge much on how this conversation developed or concluded, but stated that he became an atheist, which he remains to this day, and that had solved the problem. I’d have appreciated more detail, but maybe Telegraph readers wouldn’t. In any event, we weren’t informed on this occasion what evidence had or had not been forthcoming about the Bible’s reliability.

As I type, I recall listening to another story from a radio interviewee who had also grown up in but abandoned the Plymouth Brethren sect. He stated ‘There are lots of religions in the world, they don’t all agree so they can’t all be right, so probably none of them are.’

By all means, let us have the freedom to choose our beliefs, and whatever Christopher Hitchens and others say in denial, atheism IS a set of beliefs. At the very least, the professing atheist is asserting that he believes that the evidence for God is so weak that God can be dismissed from consideration, and also that he believes that our existence (cosmos, time, space, matter, energy, fine-tuned laws of nature, biosphere, humans and consciousness) can be satisfactorily explained without God. I would (and do) argue that both of these beliefs are wholly inadequate given what we know. I don’t know what evidence Follet thought was on his side in the conversation with his father.

C S Lewis wrote that he was against compulsory religion and theocracy. But given the claims made by and about Jesus of Nazareth, and given that Pascal’s Wager is still on and we all must and do wager whether we have thought it through or not, I can’t help feeling that (based on the little I know) both of the above gentlemen may have dismissed the case for Christianity being true too lightly.

Lewis wrote that an atheist can no more abolish God by saying ‘I don’t believe.’ than a lunatic can abolish the Sun by scribbling the word ‘darkness’ on the wall of a room in the asylum. And as to the argument that because religions make competing truth claims therefore all can be considered false, is a wholesale denial of truth. All truth claims compete with others, it is possible as any mathematician knows (Pascal was a mathematician as well as a philosopher and Christian) that out of 1,000 answers only one is correct. The fact that the other 999 are wrong doesn’t mean that the 1,000th is wrong too.

In a conversation between two men, a chemist and a sociologist (both atheists as it happens) in Lewis’s novel That Hideous Strength, they are arguing about a particular matter about which the chemist (Bill Hingest) has reached a firm conclusion. The sociologist (Mark Studdock) says that he supposes that there are many different answers to any given problem. ‘Maybe’ replies the scientist, ‘Until you know the answer. after that, there’s only ever one.’

We may choose a piece of music, a holiday or a painting based on our preference, and nobody can say we have made a bad choice even if they would have made a different one. But when we are talking about our very existence, our origin, our destiny, and the possibility (let’s assume for the sake of argument it is only a theoretical possibility) of our being accountable to a Creator, Lawgiver, Judge who has absolute authority over our eternal destiny-shouldn’t we make a very careful evaluation of the evidence? For all I know, Follet has done so, but from his reported words he gives the impression that he abandoned Christianity in favour of atheism as a matter of personal preference and because he didn’t enjoy churchgoing. You can’t establish that atheism and all that goes with it is true by simply stating that you are an atheist.

Pascal’s Wager is a philosophical construct which sets up an either/or situation in which there either is, or is not, a God who will judge us in eternity and send our undying spirit to heaven or hell based on how we conducted ourselves during our Earthly lives. We must wager for or against there being such a God. The atheist is wagering the pleasures of atheism for a limited number of years of his life if he wins the wager (there being no God) versus eternal damnation if he loses the wager. The Christian (for the sake of the wager we assume that Christianity is true and that the believer is sincere and authentic and therefore gains the promises of Christ) is wagering whatever temporary discomforts that might result from the outworking of his faith during the years of his life, against everlasting joy in the presence of God, his Redeemer, if he wins the wager. If he loses (there is no God) then he passes into everlasting non-existence and knows nothing about it.

It can be seen that the Christian who wagers will, at worst, deny himself certain questionable pleasures (intoxication, adultery, theft, gambling, lying, cheating, addiction to junk TV and porn, cursing??? and of course he doesn’t have to bother with going to church or obeying any of the commandments of Jesus). But in fact the Christian way of life (if you aren’t living under persecution, which sadly many are) can often be very pleasurable compared to that of the unbeliever. Mine is anyway. Jesus said that His yoke was easy and His burden light. And if the Christian believer loses his wager, he will simply fall asleep forever and never know anything about it. This is the worst he has to fear, and the best the atheist can hope for. On the other hand, if the atheist loses Pascal’s Wager, he will have all eternity to curse his culpable folly. Pascal argues therefore that the odds are stacked so heavily that we all ought to wager on Christ.

Of course, there are weaknesses in Pascal’s Wager, for example what if Islam of Buddhism are better representations of reality than Christianity, what forms of Christianity do you mean, and the idea that we should believe in and follow Jesus just because of the threat of damnation are all issues that could be discussed, but nevertheless I would argue that the overall construct is at the very least a reasoned theorem to make us think very hard before we dismiss Jesus of Nazareth with out doing some pretty serious due diligence.